Hi Myriam, thank you for joining me today. Can you tell us a bit about yourself?

Sure, so I’m a writer and researcher. I’m from Lebanon and I’ve been on the move in Europe for three years now. I’m interested in exploring the ties between the image, death and memory on a societal level.

So this is my main subject of research and also of writing. That’s Image, death and memory.

So this under the radar exhibition here in Geneva is part of an international project, as you know, with previous exhibitions in Medellín, Cúcuta and Nairobi. What drew you to join this exhibition in particular?

Actually, I was a bit out of my comfort zone when they contacted me saying we’re going to work in Geneva because I know nothing about the city. And also for the subject, digitalization and surveillance also for me, it was very far from what I was working on.

I was interested in exploring it further because I know it’s a subject of interest to many now and it’s becoming more and more an issue, not only a subject that we need to deal with. So this is where it started and I think now by the end of it, I managed to link both this subject and my own work in some ways.

What were the links?

So actually, when I first came, I had in mind that I’m going to work on intimacy and how people are losing intimacy and all of that. And then I was like, out of subject because people.

Before we started talking about what digital surveillance means to you? Or what does camera surveillance mean to you? Do you think this is secure or unsecure? When we started talking to people, they were unaware of its impact.

So I was like, I’m not going to work on something if the people haven’t started thinking about it yet. So this was my starting point. I wanted to include the people because all my work needs to be participatory, otherwise it’s going to be like I’m talking in the clouds to the clouds.

And in talking to people in a meeting with people, I felt like there’s a link between I mean, digital surveillance affects us all, but in terms of migrant communities and people who are strangers to the city, like me, because I came here, I didn’t know anything about the city.

So I was like, stop looking at everybody else and start thinking from inside to the outside. So I was a stranger to the city and they were too. So talking to them and learning more from experts about how these technologies affect migrants and asylum seekers in specific ways because every country is now putting up these digital walls to watch over them.

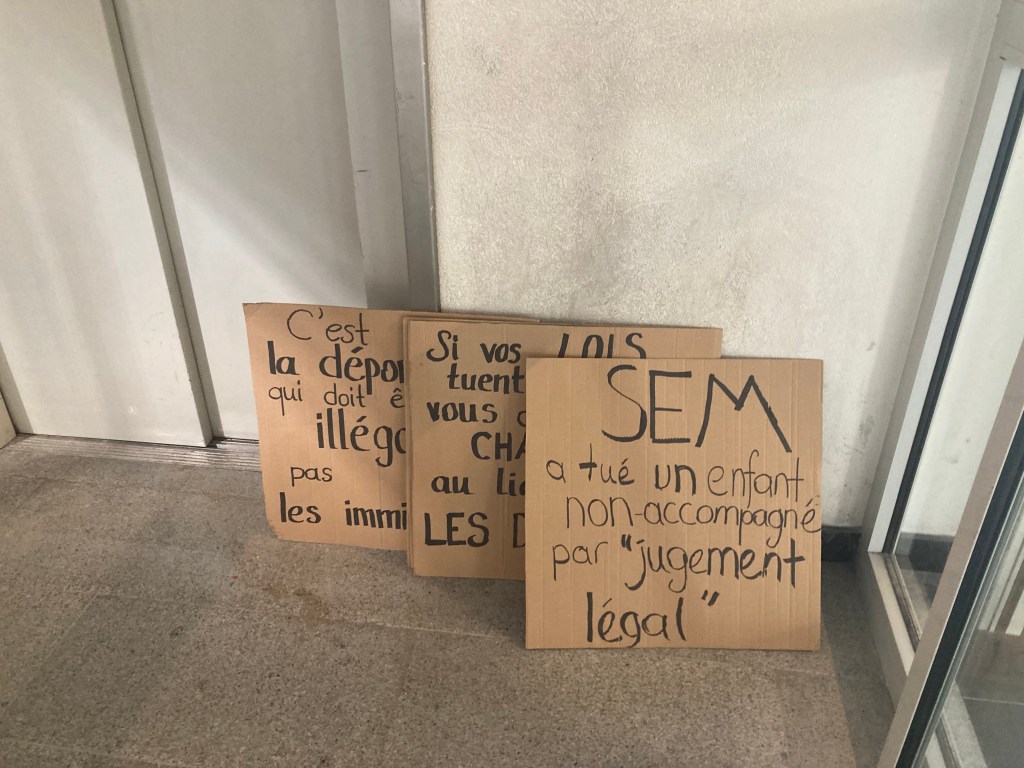

So I wanted to focus on that. And from that I learned a lot. Like, I read the text by Ama that I’m going to print, and I’ve translated in many languages for other people to read. Also, this text, like, shook me. So at first I was saddened by it. Then I was provoked. I was like, I’m not going to leave this here. We’re going to move from that. And the story that Ama reported had to do with an asylum seeker. His name is Aliresa. He suicided in 2022 in one of Geneva’s detention centers.

And I was like, there’s a lot that the city is not telling us. So we’re hearing a lot from the city the whole time, do this, do that. Walk here, don’t walk here.

So even walking in the street, I was like, we have so many marks and visuals to tell us what to do, but us, the people, have no space to speak to the city. So I started thinking about a way to talk to the city, to have the space to express ourselves, to see these stories that are under the radar come to the surface. And this is what I’m going to try to do here.

So, a major theme in this exhibition is exploring security and safety. What does security mean to you?

Yeah, I didn’t want to give it some thought on my own. I was trying to ask everybody else, because for me, I didn’t have a definition for it. So I ran to everybody else. I was like, oh, this is what it meant to them.

But then I had to reflect. I cannot be a hypocrite, asking people to define it without me being able to define it. So I think for me, security is a mix of safety and privacy, intimacy and stability.

And talking to a lot of people in a situation that’s maybe similar to mine, there was a feeling of insecurity that was constant. And this was something that I wanted to explore further. Also, like, we are in relatively secure countries, but how come we don’t feel that security?

So, yeah, this is when I was like, okay, let’s put pins on the words that are linked to security. Let’s see how come we are not feeling secure? And this is like the combination of things that I tried to link to the word itself.

Fantastic. And as many artists explore a sense of belonging. I remember last week at the public discussion you were talking about how people who don’t have passports find them in books. And with relation to art and sense of belonging, where have you found that? If not, where have people that you’ve come across found that sense of belonging?

I think that I’m trying to get accustomed to the fact that this is going to be constant. At first I was looking for an endpoint.

Now I’m like, maybe there is no endpoint. Maybe this is what it was and what it is and what I need to live with. So this feeling of belonging is perhaps now more focused on connecting. So wherever I am, whatever the situation was getting to keep me is connecting to people.

Be it through books and through hearing about other people’s stories or connections with the communities, connections with friends, people we meet. And this is where art comes, even if art, like, in its contemporary definition, is very far from what we had in mind.

When I speak about art, I speak about this. It’s the communication, the connection. And this is where we’re going to meet. It’s not going to be a place. It’s going to be a situation.

A situation, cool. Lastly, with this collective space being temporary, as an artist, what permanence would you like? What would you like there to be after the exhibition?

I love that question!

I don’t know how you’re going to include that voice stone in the written part. Exclamation. [Laughs]

Yeah, the piece that I prepared is actually a call for action. I’m suggesting a law, a bill by which we will be asking the city of Geneva to dedicate a space in the public space to put up a picture of an asylum seeker or a migrant that was either expelled, mistreated or suicided, and to post their stories.

These spaces that the city would have to dedicate for us is going to be an exchange of every five square meters, where we would find two cameras. So they’re putting up cameras. We want them to put at the surface what they’re doing. So they’re exposing us. We’re exposing them. I think it’s a fair trade and as a continuity. I’m going to be asking people to sign the petition during the exhibition. And I’ve already contacted many organizations that are really interested in taking this further.

So I’m going to follow up with them, be it NGOs, activists, political parties, or even interested individuals in the subject who would like to take this bill further.

We had two weeks and a half to work on this, and I think it was a really short time to have to learn and produce but I’m very excited about what’s coming after. And even if I’m not going to be here in Geneva, I’m going to follow up in this. I’m going to make sure I have a network that is invested as I am in this bill, and we’ll take it from there.

And your work for this exhibition?

It’s going to be a video in which I’m explaining the proposal that I have in four different languages: Arabic, English, French and Spanish. I’m also putting up a poster of Alireza, who all of this was based on what I read about his story.

So it’s going to be facing the screen for people to see. And then I’m going to add booklets from a writer called Ama. It’s the text that I read in which she tells her story as an asylum seeker in Switzerland.

It’s also going to be translated into French, English, Arabic and Spanish. And the petition is going to be there for people to sign. So it’s a multimedia call for action thing.

Amazing. Well done.

Thank you.

For more info on Alireza, read the articles below:

Suicide d’un jeune requérant d’asile: ses proches déposent plainte à Genève

Nous aurions tous pu finir par nous suicider, dans ce centre d’asile