“Hesas’lede” is a term referred to the youngest child in an Eritrean home. The most adored, often spoilt, independent and arguably the sharpest, quickly learning from their older siblings. Meticulously absorbing their surroundings, they might be the first to greet guests and assist them without a second thought. Some hesas’lede were freer than their older siblings, as everything had been tried and tested before them. Their parents,- now a lot more comfortable with parenting- naturally eased the pressure on their youngest, leaving them pressure-free. Giving them the green light to be the cool, cheeky kid that’s always playing with the local kids. Unattended, hours upon hours pass, with them exploring their neighborhoods and villages. Despite the fun and games, they might also be regularly asked to do errands for just about everyone, referred to as “Mel’akh.” You can always rely on the hesas’lede.

As the economic and political situation tightened around the necks of families, the responsibility of the hesas’lede grew. With many in the towns and cities now queing up for basic necessities and selling goods on the streets on behalf of their struggling families, to make ends meet. Similarly, with untitled lands, low food production and emptying farms, many of the hesas’lede in the rural areas skip school all together to assist their families.

Who else will do it? Once upon a time their fathers, older brothers and sisters became conscripts in the infamous, indefinite national service and never returned home. Most fled to neighboring countries, many are wandering the streets of Addis, have drowned in the Mediterranean sea or are somewhere in the West. Some disappeared in one of the many gulags inside the country and maybe, just maybe one relative is still a conscript. Perhaps a distant cousin. Many learnt the hard lessons from their older siblings, saw their bleak futures and fled. Adapting to their era, the hesas’lede went from exploring their neighbourhoods with the local kids to brutal conditions in military camps and fleeing from the local gang. The regime’s infamous MPs. Members of parliament? Ha! Nope, still no parliament. The Military Police.

The absence of their older family members has led to a generation of children overwhelmed with the burden of financially assisting their mothers, grandparents and relatives. Robbed from their childhood, they were forced to grow up fast. As soon as they hit puberty, their biggest concern is unlike most teenagers. It’s the fear of that God forsaking shida and camouflage uniform.

The hesas’lede went from helping Mama with the annoying daily errands to now helping their President achieve his meticulously planned dream: King of the Horn. Quite a leap.

Flashback

Summer 2008, Asmara. One morning over an extra sugary Lipton tea with ketcha, I had an interesting chat with a distant relative (an 11th maybe 12th cousin). We’ll call her “Saba X”, about her child. Let’s call them “Meron X.” Protected by the walls in the kitchen, our conversation secured, shortly turned to the usual “eziom” rant. Attempting to reassure her with my teenage optimism, my voice shifted to a much higher pitch,

“Don’t worry, Meron X will not go to Sawa….they will go to Asmara University instead…In ten years DIA will be gone, trust me…” Awkwardly hoping to convince her.

“Ayeeee” she tutted. Saba X was neither convinced nor enthused.

Ironically, Meron X turned 17 in 2018, the year of peace but still went to Sawa that “Ay’kesernan” summer. His/her parents are left praying they do not end up in the latest war. Lets keep in mind Meron X’s father fought (and was injured) in the other war (1998-2000).

Like a raging addict that couldn’t resist, Eritrea’s finest architect got bored of all the peace talk and resorted back to old habits. And so, born at the wrong place and time, the hesas’lede, like Meron X, are the latest generation to fall victim to Eritrea’s “Kubur President.” For the Squid Game fans, that’s the ‘Oh Il-nam’ of the Horn.

Someone’s something

Perhaps the symbol of the “hesas’lede’ (in the latest war at least) was prisoner of war Rodanim Yemane, the 16-year old Eritrean teenager from Arbate Asmara, who found himself fighting in Tigray, after being kidnapped from his home and forcibly trained for two months. At the height of Covid-19 and a time when schools, businesses and the entire country was closed- justifiably this time- the government thought it was a great idea to brutally invade, joining the Ethiopian inferno. Not with the older children, no. This time it’s harder. The knife, slightly sharper. It’s the youngest. In many cases, the same kids that were helping their families and caring for their elderly grandparents. With no end in sight, off to a land of known and unknown languages, stunning, wide green landscape, the hesas’lede advanced further to the deep south.

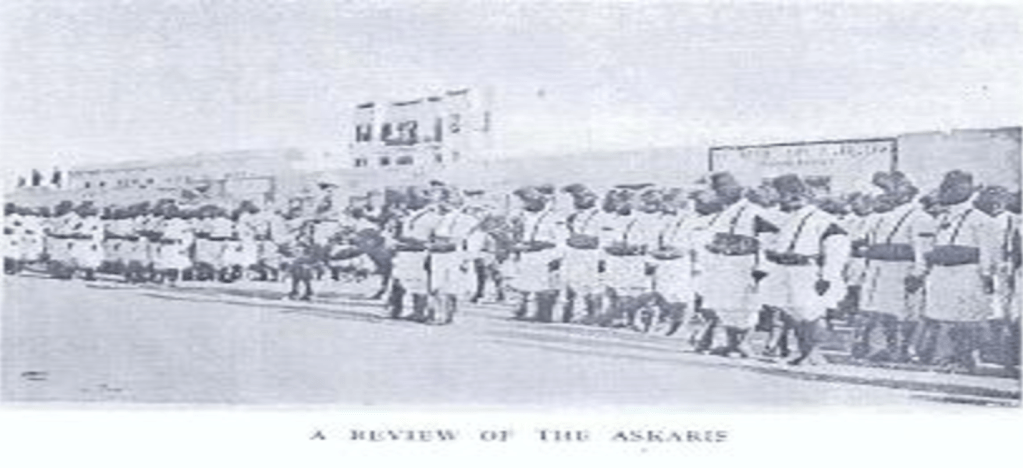

Rodanim’s generation were certainly not the first to wake up to someone’s war. There was the mobilization of young Eritreans during the 1930s. Snatched from their villages, young shepherds went down South at the will of the fascists of the day, to oust Jah Rastafari from power. Prior to that there was of course Libya, where Eritrean “Askaris” went further North in an attempt to expand the Italian Empire. We had the Italians seeking vengeance for the Battle of Adwa and now Dear Isu seeking vengeance for the Border War and his post-war isolation. Potai-toe, Pataa-ta, tomai-toe, tomaata.

Again, someone else’s vengeance and expansionist dreams and nothing to do with neither Weldenkel nor Awet.

Kids

But back to the kids of the latest war.

Rodanim and fellow conscripts were led into this war by men old enough to be their Grandfathers. Usually when people get to retirement age they go all out. Perhaps on a long cruise to the Bahamas or Bali, move to the suburbs, have cozy lie-ins, maybe a cold beer at 10am, watch a bit of TV and meticulously attend to their plants. Their biggest irritant of the day might be the insects that destroyed the fruits in the back garden. Damn them!

On the one hand we saw what was thought to be the World’s Oldest man aged 127, die peacefully in his village in Eritrea, breaking international news. Peacefully being the keyword here. And on the other hand we have Isaias and his aging PFDJ officials well into retirement age, with jet black hair dyes, clinging onto dear life at the cost of their Grandchildren.

That scene in Coppola’s The Godfather comes to mind. Marlon Brando’s Don Corleone is spending quality time with his Grandson Anthony (Michael’s son) in their garden. To be fair to him, totally normal behaviour. Fruits and wine at the table, with a comfy armchair as the Don cuts a lemon, he attempts to amuse his grandson by putting a slice in his mouth, covering his teeth. For a moment Little Anthony is frightened and begins to cry to which Grandpa immediately comforts him, encouraging him to play on. There is an innocence and playfulness to the Don that is unrecognisable. For the softies, the scene is indeed touching and as the movie’s protagonist, we’re convinced to empathise and even be sorrowful for his inevitable end.

As a much frail Don attempts to play with little Anthony waving a toy gun, he starts to lose him through the enormous, wavy lemon plants, taller than the Don himself. Pulling silly faces at his Grandson, the Don begins to noticeably stagger, coughing uncontrollably he falls backwards. Little Anthony inherits the same innocence of his Grandpa. Thinking it was all part of the game he giggles, runs to the now lifeless Don as he aims the water gun at him, he proceeds to squirt water at his Grandpa. After a brief pause, watching over his Grandpa, he contemplates the deafening silence and wobbles away for help.

Although still young, Anthony was fortunate enough to have some fond memories of his grandad. In comparison, such memories are short-lived in Eritrea, as grandparents continue to watch their children flee from their homes. I know what you’re thinking, “but but… Dear Isu had a cute scene with his Granddaughter too. Do you remember her sitting on his lap when Abiy came to visit?” Yeah, no, not quite the same.

Growing seeds

The pro-Eritrea advocates and parliamentarians of the 1940s and 1950s were graceful and long-sighted enough to inspire and support their children and grandchildren. Such wisdom and vision inspired the revolutionaries of the 1960s and 1970s. Visionary leaders such as Aboy Woldeab Woldemariam, Aboy Ibrahim Sultan and Hamid Idris Awate inspired the thousands of tegadelti (fighters). Committed revolutionaries such as Osman Saleh Sabbe, taught and inspired prominent fighters, prior to them joining the movement. These seeds of revolutionary wisdom, passed from one generation to the next, skipped a generation or two and might just be the missing piece in the puzzle. Unfortunately today’s Grandpas at the helm of power never inherited their predecessors’ class. Instead, denying the younger generations the same wisdom they inherited, condemning them to indefinite national service, whilst closing Asmara University. Throughout the years, as Eritrea’s Oh Il nam waged war with his neighbours, he also brutally waged war on the country’s most precious group in need of nurturing: the youth.

Perhaps with more graceful and forward-thinking Grandpas, Rodanim and peers will only worry about how to grow a beard or when their voices will break.

P.s. Album of the week:

Fela Kuti – Teacher don’t teach me nonsense (LP), 1986

References:

- Ethiopian and Eritrean Askaris in Libya (1911 – 1932), Dechasa Abebe, 2017

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Corps_of_Eritrean_Colonial_Troops

- HRCE, “Eritrean Underage Boys “Press-Ganged” into Military and Sent to Tigray to Fight”, March 30 2021

- Osman Saleh Sabbe, Wikipedia

- Image Pen Eritrea: “Woldeab Woldemariam: A Visionary Eritrean Patriot, Biography”, Dawit Mesfin, 2017